This article sheds light on a little-known chapter of Colorado’s prison history, raising critical questions about the role of private prisons and the treatment of incarcerated individuals.

“ While awaiting the completion of the above mentioned expansions and new facility, and with the declining availability of state or private beds, it was inevitable that the CDOC would need to go out of state for beds. In December 2006 and January 2007, the CDOC sent 480 inmates to the North Fork Correctional Facility in Sayre, OK. It is a CCA owned facility. The Private Prisons Monitoring Unit has two monitors assigned to the facility at any given time. They operate on a two week rotation and reside in Sayre during their rotation. The assignment is typically for a 3-6 month period and then new monitors are assigned. The other members of the unit-such as the medical, mental health and food services liaisons routinely make monitoring visits to NFCF as well. It is expected that the CDOC will likely utilize the North Fork facility for at least one more year. The Colorado PPMU has been recognized nationally as a model in progressive contract facility management. The unit continues to be called upon by other agencies for feedback and information by those who are interested in pursuing or improving contract housing services for their inmates. Officials come to Colorado to discuss our procedures and experiences and tour contract facilities in Colorado. “ Trevor Williams 11.15.2007.

At some point in Colorado’s history, the Department of Corrections (DOC) claimed overcrowded prisons as the justification for a peculiar and largely unpublicized operation: transferring over 500 inmates from Colorado to a private prison in Oklahoma. It raises an important question—was this truly a logistical necessity due to an unforeseen rise in inmate population, or was it a calculated financial decision to exploit a lucrative opportunity outside state lines?

The Hidden Details of Colorado’s Transfer

In 2006, the Colorado DOC transported hundreds of inmates to the North Fork Correctional Facility, a privately-run prison in Sayre, Oklahoma. Official reports and media at the time cited figures as low as 240 inmates, but those who experienced the move firsthand suggest the number was significantly higher, exceeding 500 men. The move was not widely publicized, and the details surrounding it remain murky.

A Surprise One-Way Ticket

Inmates weren’t given advance notice about their relocation. On the morning of the transfer, they were told to pack their belongings and loaded onto buses or vans without being informed of their destination. For many, it wasn’t until they boarded a plane or endured hours shackled in small transport vehicles that they learned they were leaving Colorado altogether.

For those on the bus journey, the experience was harrowing. Shackled in “black boxes”—restrictive restraints designed to prevent movement—they sat shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers for over 20 hours. Their only stop was at a remote jail in the middle of nowhere to use the bathroom. The physical discomfort was compounded by the anxiety of not knowing where they were headed or how long they’d be gone.

The Oklahoma Skittles Yard

The North Fork Correctional Facility was unlike a traditional state prison. Instead of housing inmates from Oklahoma, the compound served as a melting pot for prisoners from various states. Colorado inmates stood out in their green uniforms, while others wore gray or different colors, depending on their state of origin. One inmate described the yard as resembling “a bunch of Skittles scattered on the ground.”

This arrangement created a unique prison environment, with individuals from different jurisdictions learning to coexist under unfamiliar rules and conditions. Communication between inmates became a lifeline, as many were left to guess how long they’d be held in Oklahoma and whether they’d ever return to Colorado.

Lack of Transparency and Accountability

The secrecy surrounding the transfer raises concerns about transparency within the Colorado DOC. Why wasn’t the public informed? Why weren’t families of the inmates given prior notice? Even today, a deep dive into available information reveals little about this controversial move. It appears that the DOC preferred to keep this chapter of its history out of the spotlight.

Moreover, questions linger about how the DOC miscalculated its inmate population so severely that it resulted in “overcrowding” and necessitated shipping inmates to a private prison out of state. Was this an administrative failure, or was it an intentional strategy to offload inmates in exchange for financial savings or benefits?

The Human Cost of the Transfer

For the men who were relocated, the experience was dehumanizing. Many were selected based on good behavior and health, as private prisons often reject inmates with costly medical needs or disciplinary issues. Paradoxically, this meant that well-behaved inmates were effectively punished by being sent farther away from their families.

Family connections play a crucial role in reducing recidivism, yet this move severed those ties. One inmate shared how the transfer destroyed his chance to build a relationship with his two-year-old twins. “I was ripped away from them,” he said.

Seeking Answers

This unsettling chapter in Colorado’s corrections history demands further investigation. How could the DOC have so poorly planned for its inmate population? Why were families and the public kept in the dark? Was this move truly about overcrowding, or was it driven by profit motives tied to private prison contracts?

I’ve reached out to officials in Oklahoma for clarification and await their response. The lack of transparency surrounding this operation, coupled with the human toll it took on inmates and their families, warrants greater scrutiny.

It’s time for Colorado to confront this forgotten episode and ensure that such actions are never repeated. Prison operations should prioritize rehabilitation, transparency, and family connections—not profit or expedience.

On a frigid January morning in 2007, a high-security operation unfolded at Pueblo Memorial Airport. Correctional officers clad in black, armed with pistols and assault rifles, escorted 120 inmates—killers, robbers, and drug offenders—from buses and vans to a Champion Air passenger plane. The inmates, shivering in below-zero temperatures, were shackled, chained, and frisked for contraband before boarding the flight. Their destination: North Fork Correctional Facility, a private prison in Sayre, Oklahoma.

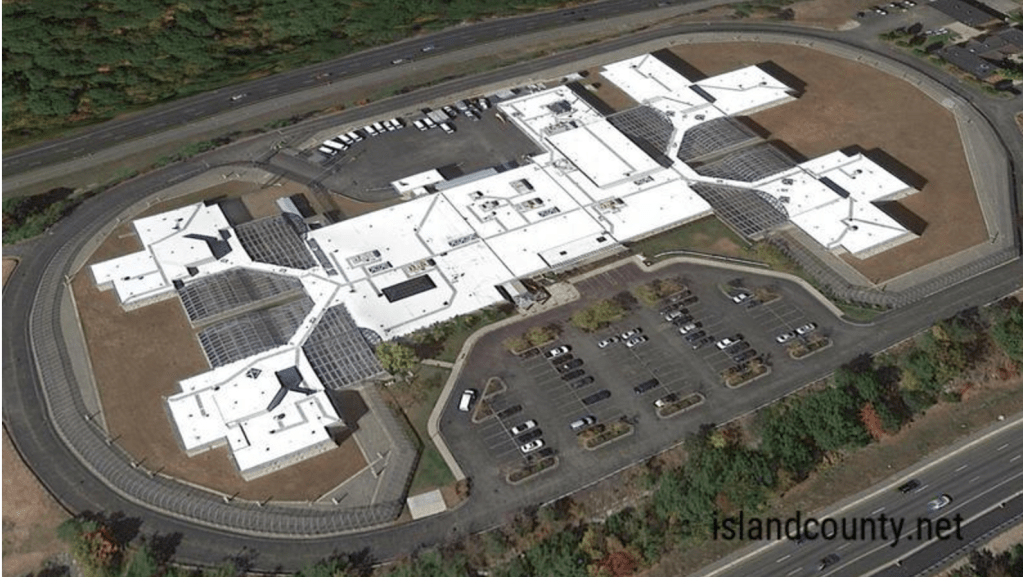

North Fork Correctional Center, located east of Sayre in Beckham County, Oklahoma, is a medium-to-maximum security prison originally built in 1998. Initially operated by the private entity Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic), the facility housed inmates from various jurisdictions, including California, to address overcrowding in their prisons. This arrangement lasted until 2015, when it was closed following the end of private operations. The facility reopened in 2016 under the management of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections (DOC) as part of an effort to address the state’s prison overcrowding crisis. Oklahoma leased the facility for approximately $7.5 million annually, though the first 18 months of the lease were rent-free. With a capacity of up to 2,600 inmates, including units for medium and maximum security as well as a segregation unit, it became one of the most technologically advanced and largest prisons in Oklahoma.

For many, the operation symbolized a grim turning point in Colorado’s efforts to manage its burgeoning prison population.

The Transfer: A Necessary Evil?

The transfer was part of Colorado’s response to a growing inmate population, which was increasing by 100 per month and had pushed the state’s facilities to capacity. “We don’t have another option,” said Gary Golder, director of prisons for the Colorado Department of Corrections (DOC). The North Fork facility, operated by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), was contracted to house up to 720 Colorado inmates at $54 per day per prisoner.

However, the move came with significant drawbacks. North Fork only accepted inmates in good health and with good behavior records, creating resentment among those who felt they were being punished for complying with prison rules.

“We’re not trying to penalize them,” Golder insisted. But for inmates like convicted robber Christopher Acuna, who was separated from his young children, the transfer felt deeply personal. “I was hoping to have some type of relationship with them. This stopped that,” he said.

On January 17, 120 inmates from nine Colorado prisons were transported to the Pueblo airport for the flight to Oklahoma, joining 240 inmates sent in December. At Limon Correctional Facility, 17 inmates learned of the transfer just one day before, with phone access restricted to prevent communication with family.

Conditions at North Fork

Upon arrival, inmates were immediately subjected to a five-day lockdown to acclimate them to the facility’s rules. While North Fork offered some vocational training and limited employment opportunities, the inmates voiced widespread dissatisfaction with the conditions.

Food quality was a primary concern. Meals, described as small and lacking in variety, sparked numerous complaints. “My niece eats way more than they’re feeding us,” said Eugene Mason, who was serving time for robbery and accessory to murder.

The facility’s operations, too, were criticized. Inadequate staffing often led to frequent lockdowns, and a lack of programming options left inmates with little to do. These issues mirrored those at Colorado’s Crowley Correctional Facility, where riots in 2004 were sparked by similar grievances.

Separating Families: The Human Cost

For many inmates, the transfer severed vital family connections. Research shows that maintaining family ties can significantly reduce recidivism, yet the move made visitation nearly impossible. To mitigate this, the DOC promised to implement video conferencing, allowing families to connect with inmates remotely.

Still, for inmates like Acuna, the emotional toll was devastating. “I wanted to watch my kids grow up,” he said. “Now, I don’t know when I’ll see them again.”

A Troubling Trend

The transfer to Oklahoma highlighted the growing reliance on private prisons to address overcrowding, raising ethical and practical concerns. Unlike Colorado’s state-run facilities, North Fork was not required to meet the same programming standards, leaving inmates with fewer opportunities for rehabilitation.

The DOC deployed two monitors to oversee conditions at North Fork, but questions remain about the adequacy of their oversight. While DOC spokesperson Alison Morgan praised Warden Fred Figueroa for his proactive leadership, many inmates felt their grievances went unheard.

Morgan countered that the meals meet Colorado’s nutritional standards, even if they provide fewer calories—2,400 per day compared to 3,000 in Colorado prisons. “Get used to it. You’re in prison,” she remarked.

Colorado’s Interstate Inmate Transfers: A Controversial Chapter in Prison Management

In the mid-2000s, Colorado grappled with prison overcrowding by transferring inmates across state lines. These moves sparked significant controversy, raising questions about the motivations, treatment of inmates, and the financial incentives underpinning the state’s reliance on private prisons.

Mississippi Transfers and Washington Relocations

Alison Morgan, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Corrections (DOC), confirmed that 128 inmates sent to Mississippi in April 2004 due to “minor disturbances and gang-related activities” were slated to return following individual case reviews.

Meanwhile, inmates from Washington state housed at Colorado’s Crowley County Correctional Facility were relocated after a July 2004 riot. The riot, involving more than a third of the prison population, caused extensive damage to housing units and facilities. By April 2005, only eight Washington inmates remained, detained on pending criminal charges.

Following the riot, Crowley County Correctional Facility shifted its focus to housing inmates from Colorado and Wyoming, with over 1,100 beds left vacant. Morgan indicated that some inmates returning from Mississippi might be reassigned to Crowley or the Kit Carson Correctional Facility in Burlington.

Private Prisons and Financial Incentives

The DOC’s heavy reliance on private prisons became increasingly evident during this period. A backlog of roughly 1,000 inmates in county jails awaiting state facility placement underscored the system’s strain. Budget constraints, longer sentences, and rising incarceration rates compounded the issue, leading the DOC to plan the transfer of an additional 1,000 inmates to Oklahoma.

State leaders, including Sen. Paul Weissmann and Rep. Buffie McFadyen, criticized the DOC for its lack of transparency and population management strategies. McFadyen emphasized the dangers of overcrowding and called for clear objectives to address the state’s reliance on private prisons.

Alison Morgan: A Polarizing Figure

Morgan’s role in inmate transfers drew significant scrutiny. She signed off on key documents related to relocations and was criticized for remarks perceived as dismissive, such as her response to complaints about poor food quality at the North Fork Correctional Facility in Oklahoma: “This is your new home. This is a prison.”

Adding to the controversy, Morgan later transitioned to a role with the Colorado Bankers Association. This career shift raised questions about whether her decisions in the DOC were influenced by financial interests tied to private prison contracts. Her involvement in managing inmate transfers and subsequent move to the private sector has fueled calls for further investigation.

The Oklahoma Experience

Interviewer: “Colorado prison, right? How long have you been there?”

Inmate: “I was in Colorado DOC for about a year and a half, maybe. Then what happened after that?”

Inmate: “One day they told me to pack up, and I thought I was going to another prison. We went to the diagnostic area, and there were, like, seven or eight of us. We hopped into a van and drove to *** in Oklahoma.”

Interviewer: “Can you clarify, you mean like a passenger van?”

Inmate: “Yeah, like a passenger van. We just kind of chuckled at each other.”

Interviewer: “Did you have shackles on?”

Inmate: “Yeah, you had an ankle shackle, handcuffs, and a chain that connected your shackles to your hands. And they kept the black box on the whole way.”

Interviewer: “So you were in a full restraint system?”

Inmate: “Yeah, the whole way. It was pretty bad.”

Interviewer: “How many hours was the trip?”

Inmate: “I don’t know, whatever it is from Canyon City to *** in Oklahoma. We did stop at one point.”

Interviewer: “Did they let you use the bathroom during the trip?”

Inmate: “Yeah, only once, and it was in a small town in Texas. We stopped at a county jail, a tiny podunk town, and they let us out one at a time.”

Interviewer: “When did you find out you were going to Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “They told us in the van. It was a security thing, they didn’t tell us earlier.”

Interviewer: “How did everyone react? Was there panic?”

Inmate: “We were all a little confused. We had heard rumors that they’d already flown a bunch of guys to Oklahoma, and we were the last group to go. But we didn’t know for sure until we were in the van.”

Interviewer: “What were the rumors about Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “They were sending people to Oklahoma because Colorado was overpopulated. That’s what we heard.”

Interviewer: “When was this?”

Inmate: “It was either 2006-2007 or 2007-2008.”

Interviewer: “Who was advocating for you guys?”

Inmate: “There was a legal guy named Jeremy Gardner. He filed a bunch of legal stuff, and everyone attached to his case with a joiner, which is a legal document.” Kidnapping.

Interviewer: “Did everyone make it back from Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “Everybody made it back, but two guys from Colorado died while we were there. One guy died from a seizure after he took nutmeg to get high, and another guy was beaten to death.”

Interviewer: “What kind of offenders were sent to Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “Mostly high custody, close custody offenders. The majority had double digits left to serve. There were some with 5 or 6 years, but most had much longer sentences.”

Interviewer: “How did families react when they found out?”

Inmate: “It was a shock for them. You just tell them over the phone, ‘Hey, I’m not in just another prison, I’m in a whole different state.’”

Interviewer: “Was this before or after Trump took office?”

Inmate: “This was before.”

Interviewer: “So, you were in prison for a year and a half. Do you think the population was overpopulated at that time?”

Inmate: “All the private prisons were full, and the state prisons were overcrowded too. I don’t think it was just about overpopulation. There was another reason, but I don’t know what it was. I didn’t think much about it at the time.”

Interviewer: “Did you think about it while you were driving to Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “No, we just went with it. We knew about the other group of people who were flown to Oklahoma before us. But once we got in the van, we realized it was happening.”

Interviewer: “What happened once you arrived in Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “They had seven jurisdictions there. There were people from different states—Colorado, Vermont, and others. It was mostly a private prison run by either GEO Group or CoreCivic.”

Interviewer: “What were the biggest differences between Colorado and Oklahoma prisons?”

Inmate: “In Oklahoma, it was all about inconsistency. There were lockdowns for no reason, and everything was chaotic. It was like, if the library was scheduled for 8 a.m., one day you’d go at 7:30, and the next day it’d be at 9:00.”

Interviewer: “What about legal matters like appeals? How did people handle them there?”

Inmate: “You just did the best you could. Case managers weren’t around much, so you just sent your stuff out through the mail slot and hoped it went through.”

Interviewer: “How were people with sex offenses treated?”

Inmate: “There weren’t many people with sex offenses there. Most were drug offenders, and it was pretty easy to get drugs in the prison.”

Interviewer: “So, what’s the biggest difference between state prisons in Colorado and Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “Oklahoma was mostly private prisons, with inmates from many different states. If you looked from the sky, we probably looked like a bag of Skittles, with different colors representing each state’s inmates.” There was 7 jurisdiction, mainly California.

Interviewer: “Do you think people should know about the situation in Oklahoma?”

Inmate: “Yeah, it’d be good to figure out why we were sent there. After we came back, everyone went to either Burlington or Bent County, both private prisons. But after that, nothing like it happened again.”

Interviewer: “How did families react when you came back?”

Inmate: “They were glad we were back in Colorado. Visits were much easier, and a lot of people got to see their families again.”

Interviewer: “How did you get back to Colorado?”

Inmate: “We were escorted to an airfield in Oklahoma, then flown back by U.S. Marshals or someone else. It was strange, but I’m not sure who exactly escorted us.”

Interviewer: “So, if there had been a kidnapping charge, could Oklahoma have touched you physically?”

Inmate: “I don’t know. It’s complicated, but I do think we were ever officially ‘kidnapped.’”

The Ongoing Crisis in Colorado’s Prison System: A Call for Accountability and Change

In the mid-2000s, Alison Morgan, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Corrections (CDOC), made a troubling statement: the state didn’t have enough money to hire more guards, despite the approval of new private prisons with a staggering 3,776 beds. This statement, made around 2006 or 2007, highlighted a systemic issue that has plagued the prison system for over two decades. Over the years, the problem has only worsened, and today, we are left grappling with a situation that shows no signs of resolution.

Morgan’s prominent role in inmate transfers, coupled with her transition to the banking sector, raises concerns about potential conflicts of interest. Was financial gain prioritized over inmate welfare? How deeply were private interests embedded in the DOC’s decisions? These unresolved questions demand further investigation into Colorado’s handling of inmate populations during this contentious era.

The facts are clear—Colorado’s prison system is overcrowded, underfunded, and failing to meet the demands of a growing incarcerated population. The recent passage of Proposition 128 in 2024 has only exacerbated these issues. This measure increases the time that individuals convicted of violent crimes or habitual offenders must serve before being eligible for parole. Violent offenders must now serve 85% of their sentences, and habitual offenders are required to serve 100% before being considered for parole.

While proponents of Proposition 128 argue that it will increase public safety, the reality is that it will likely lead to even greater overcrowding in an already strained system. According to data, by 2026, the inmate population in Colorado is expected to reach around 21,000—nearly 5,000 more than current capacity. This means the state will either need to build new prisons or face the prospect of overcrowded, inhumane conditions, much like those endured by prisoners in the past, including those who were shipped to private prisons in Oklahoma under deplorable conditions.

The underlying issue is not a lack of commitment from the CDOC, but rather the failure of advocates and policymakers to understand the long-term consequences of their decisions. The state is caught in a vicious cycle, where building more prisons and imposing harsher sentencing policies only increase the burden on a system that cannot handle the demand. We are left asking: is the solution really to continue expanding the prison system, or is it time to explore alternatives such as reducing the prison population or increasing wages for correctional officers to attract and retain staff?

The failure to adequately address the problems within the system lies, in part, with the very advocates and activists who claim to champion criminal justice reform. In 2024, many of these groups pushed Proposition 128 without fully understanding the impact it would have on the state’s prison population or the resources required to manage such a surge. As someone who has worked on criminal justice reform, I can say that we need a more proactive approach. Advocates must work years in advance, building awareness, and pushing for reform before it becomes a crisis.

Unfortunately, the approach in Colorado has been reactive rather than proactive. Many of the activists, particularly from younger generations like Gen Z, seem ill-prepared to tackle the complexities of the criminal justice system. While they have access to social media and can mobilize quickly, they lack the depth of understanding and experience needed to effect lasting change. This has created a disconnect between the younger generation pushing for reform and the older demographics that vote on criminal justice issues. Those between 40 and 60 years old make up a significant portion of the electorate, and their voices will continue to be a major factor in shaping policies that affect the prison system.

Moreover, many of the advocacy organizations and coalitions, despite receiving large grants and funding, appear to be failing in their efforts. They have fancy offices and high-profile figures associated with their causes, but the real work needed to advocate for meaningful change seems to be lacking. Instead, we see more attention given to individuals and organizations that prioritize personal agendas over systemic reform. For example, the influence of figures like Mr. [Name] from the Second Chance Center, who seems to be involved in every aspect of criminal justice reform, is worth questioning. His actions and influence raise concerns about whether these groups are truly working to address the root causes of over-incarceration or merely pushing their own interests forward.

The truth is, Colorado’s criminal justice system is at a crossroads. We cannot continue down the same path of expanding the prison system while failing to address the root causes of crime and incarceration. There needs to be a shift in how we think about crime, punishment, and rehabilitation. We must ask ourselves: Do we want to continue building more prisons, or do we want to invest in alternatives that reduce recidivism and offer people a second chance at life?

As we look toward the future, it’s crucial that we demand accountability from all parties involved. The state, the CDOC, the advocates, and the public must come together to find a solution that prioritizes rehabilitation over punishment and addresses the structural issues within the prison system. Without a comprehensive, long-term strategy that includes prison reform, reducing the prison population, and investing in alternatives to incarceration, we will continue to face the same problems we have for the past two decades. It’s time to confront the harsh realities of Colorado’s criminal justice system and demand a better way forward.

Human Impact and Calls for Reform

Inmate transfers disrupted family and community connections, often placing individuals in substandard conditions. The riot at Crowley County Correctional Facility exemplified the instability of these arrangements, with widespread unrest and damage underscoring the risks.

As lawmakers and the DOC faced mounting criticism, Colorado’s partnerships with private prisons became a flashpoint. The events of this period underscore the importance of ethical oversight, transparency, and a shift toward prioritizing rehabilitation over profit. Colorado’s transfer of inmates to North Fork exemplifies the challenges of balancing public safety, fiscal responsibility, and human dignity within the correctional system. While the CDOC framed the move as a logistical necessity, it underscores the deeper issues of prison overcrowding and the ethical dilemmas of outsourcing incarceration to private facilities.

For the 480 or 720 or 1000 inmates because number is still unknown Colorado inmates housed in Sayre, the transfer represents more than a change in location—it’s a stark reminder of the system’s prioritization of efficiency over rehabilitation and connection. As Colorado’s prison population continues to grow, the state must confront the long-term consequences of these decisions, ensuring that future policies prioritize transparency, fairness, and the well-being of all stakeholders.

In conclusion, it’s clear that there are significant discrepancies surrounding the actions of Alison Morgan. Her signature appears on multiple documents related to the transfer of inmates to Oklahoma, where she claimed that only low-risk offenders with perfect placements and no history of problems were being sent. However, the reality was far different. Lifers and high-risk offenders were also shipped out, sent to overcrowded, inhumane conditions that resembled a war zone. Now, as people try to explain away these transfers, the truth seems to be slipping through the cracks. It’s time to ask why this happened, and why some are now downplaying the situation. Allison Morgan may hold more answers than we realize, and it’s time to uncover the full truth.

Where is Jeremy Gardner …

Disclaimer: This article discusses a real story involving real people and real events. It is published with the intention of informing and raising awareness about the complexities of such narratives. The content does not intend to defame or slander any individuals, and there are no legal consequences associated with the publication of this story regarding defamation or character slander.

Leave a comment