The Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI) is at the center of a forensic scandal that has shaken the state’s judicial system. The decades-long misconduct of Yvonne “Missy” Woods, a veteran DNA scientist at the CBI, has cast doubt on hundreds of convictions, prompting calls for systemic change. A new law is in development, aiming to address the repercussions of this scandal by ensuring transparency, accountability, and justice for potentially wrongfully convicted individuals.

The Proposed Legislation

The Colorado Office of the State Public Defender is drafting legislation to be introduced in the 2025 Colorado General Assembly. Key provisions of the proposed law include:

- Enhanced Notification: Defendants affected by the misconduct would receive direct notification, rather than relying on district attorneys.

- Post-Conviction Counsel Access: Ensures that affected defendants have adequate legal representation to reopen their cases if necessary.

- Retroactive Application: The law would apply to both past convictions and future cases, signaling a commitment to justice for all impacted.

This legislative effort comes in response to revelations that Woods manipulated or deleted DNA findings in cases dating back to 1994. So far, 809 anomalies have been identified in her work, though defense attorneys argue that this number is likely a significant undercount due to limited transparency from CBI.

Governor Polis’ Oversight Committee

Governor Jared Polis recently signed an executive order establishing a 14-member committee to oversee CBI’s forensic practices. This panel will include representatives from law enforcement, the defense bar, forensic science experts, and the Colorado Attorney General’s Office. While the move aims to restore public trust and propose systemic improvements, critics argue that the committee is heavily skewed towards law enforcement interests.

Mary Claire Mulligan, a Boulder defense attorney, expressed skepticism:

“This is just more of the fox guarding the henhouse. It’s politics disguised as reform and does little for those harmed by CBI’s failures.”

The recent creation of a committee to address the fallout from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI) scandal is a textbook example of the fox guarding the henhouse. While it’s being framed as a step toward reform, the reality is that it’s yet another politically driven measure that does little to address the real harm inflicted on those affected by the CBI’s failures. This committee, heavily weighted with representatives from law enforcement and the very agencies implicated in the scandal, raises serious concerns about its ability to deliver meaningful change. How can we trust a system to police itself when the very institutions responsible for oversight have already shown a lack of accountability?

True reform requires independence, transparency, and a focus on those who have suffered as a result of these systemic failures. Yet, this committee appears more concerned with salvaging the credibility of the CBI than with delivering justice to the individuals wrongfully convicted or affected by flawed DNA testing. For those whose lives were derailed by these failures, politics disguised as reform is not only inadequate—it’s insulting.

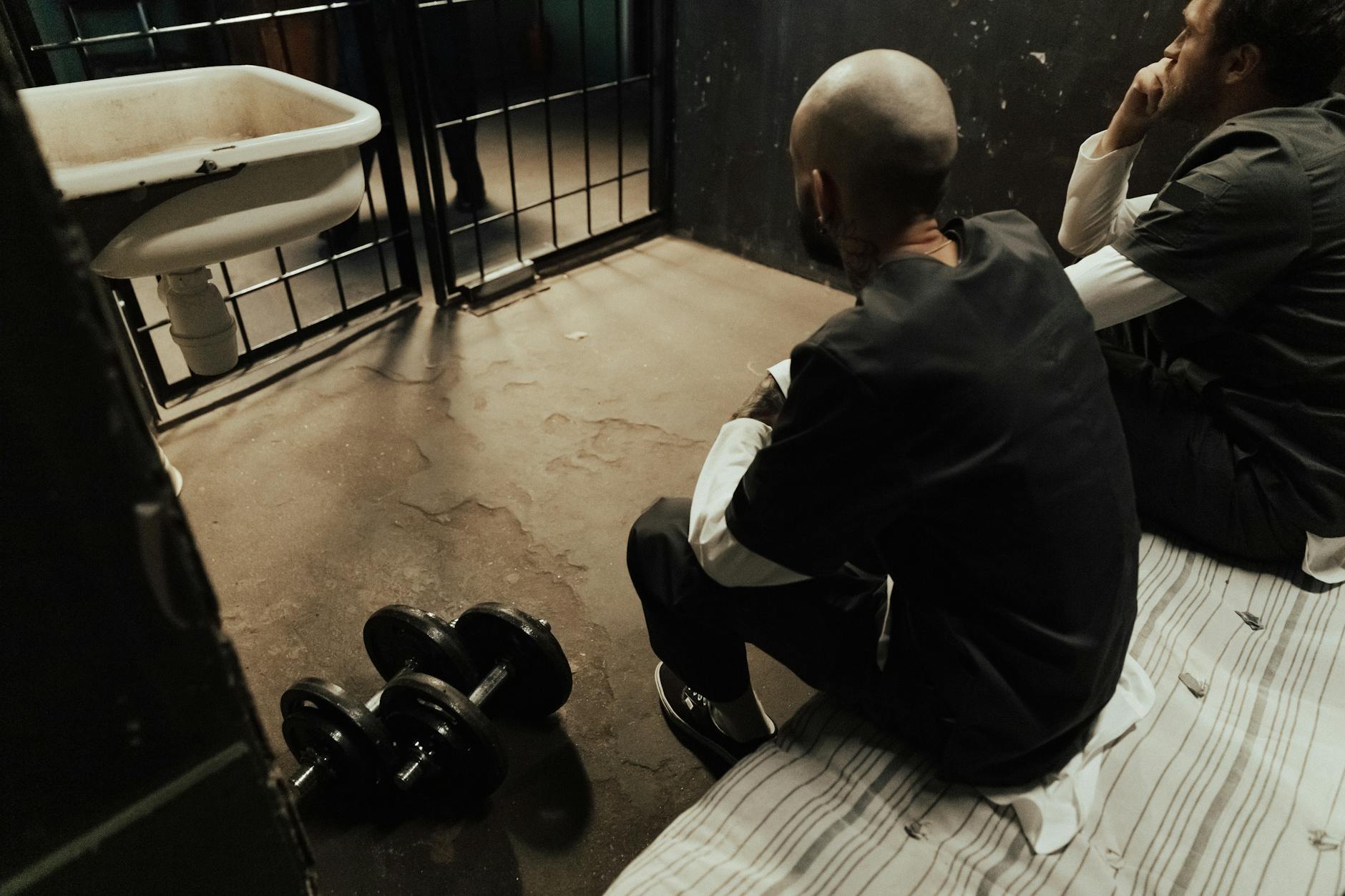

The Human Cost of Misconduct

The impact of Woods’ misconduct is not merely procedural; it has had life-altering consequences for defendants, victims, and their families. Recent cases highlight the ongoing fallout:

- James Herman Dye: Accused of murder and rape, Dye was freed after retesting excluded his DNA, contradicting Woods’ earlier findings.

- Garrett Coughlin: Originally sentenced to life for a triple homicide, Coughlin accepted a plea deal for a lesser charge after the state lost confidence in Woods’ ability to testify.

- David Hehn: Convicted in 2011 for January 1982, Fort Collins shocking murder of Gay Lynn Dixon, a bright 17-year-old whose life was taken. This was a cold case.

- Matt Long: Convicted as a 19-year-old in 2003 and sentenced to 30 years in the Colorado Department of Corrections.

These cases underscore the urgent need for reforms that prioritize the rights of wrongfully convicted individuals and ensure forensic integrity.

There are over 800 additional cases that should be mentioned by Jenny Deam, who published this article in The Gazette. It seems she is overly focused on Michael Clark’s case. Whether she’s being paid to repeatedly highlight his name or is simply fixated on it is unclear. However, it’s important to note that Michael Clark is not wrongfully convicted; instead, he’s exploiting technicalities related to Missy Yvonne Woods’ handling of his DNA evidence. His attorney, Adam Frank, has been involved in this case for over seven years, and it seems he’s looking to justify the time and effort he’s invested.

In February, we reported on Michael Clark, accused of killing Boulder official Marty Grisham in 1994, though he wasn’t formally charged until earlier this year. Despite a case built largely on circumstantial evidence, the prosecution secured a first-degree murder conviction. As previously shared, Grisham, the city’s data processing director, was shot and killed at his Arapahoe Avenue apartment on the evening of November 1, 1994. He had interrupted dinner with his girlfriend to answer a knock at the door, after which he was shot four times and later declared dead at a hospital. Attention quickly turned to Clark, a friend of Grisham’s daughter, due to suspicious circumstances. Earlier that day, Grisham had reported a stolen checkbook with over $4,000 in fraudulent charges. Clark admitted to the theft and had access to Grisham’s apartment, as Grisham’s daughter had given him a key to care for the family cat. However, Clark denied any involvement in the murder and wasn’t charged at the time. That changed in January, over two years after the case was reopened. The arrest affidavit highlighted contradictions in Clark’s accounts of how he obtained a gun prior to the murder, as well as alleged comments he made to a jail cellmate following his arrest for check theft. Initially released on a $100,000 bond, Clark’s troubles mounted when he was arrested again for drunk driving, tipped off by his probation officer. Police records revealed Clark had admitted to drinking whiskey and gin before driving to Boulder, though he claimed he didn’t drink while on the road. This slip resulted in a reduced bond of $1,000, and Clark was released again to prepare for trial. During the trial, the jury reviewed seven days of testimony and deliberated for two days. Prosecutors presented evidence that Clark had sold a 9mm gun, the same caliber used in the murder and argued that he killed Grisham to silence him and protect his plans to join the Marine Corps. Witnesses also testified to seeing Clark with a weapon before the crime. Ultimately, the jury found Clark guilty, resulting in his immediate custody and bringing closure to a case that had remained unresolved for nearly two decades.

Is this person truly wrongfully convicted, or are they merely exploiting the recent DNA scandal as a golden ticket to get out of prison? The evidence seems to speak for itself. It’s important to remember that there is a significant difference between being innocent and being guilty.

Advocacy for Accountability

Organizations like the ACLU of Colorado and the Korey Wise Innocence Project are pushing for greater oversight and transparency. They have accused CBI of failing to comply with federal grant requirements and demanded accountability for the years of forensic malpractice.

Why did the ACLU get involved a week after the election? Where were they since November 2023? Why now? Is it because the ACLU, largely aligned with Democratic ideals, is worried about losing funding under a Republican-led government? I have zero tolerance for the ACLU; it’s one of the most overly idealistic, Gen Z-style organizations in the U.S. These people seem more adept at complaining over avocado toast than effectively addressing real issues—they can’t even manage basic tasks like using a scanner.

Adam Frank, a defense attorney for Michael Clark, remains cautious about the governor’s committee: “While more oversight is welcome, entrusting insiders with recommending changes to CBI leadership seems unlikely to yield meaningful reform.”

First Concern: Audit Timeline

On July 25, 2024, CBI posted a solicitation for bids to conduct a Forensic Services Audit. The agency contracted Forward Resolutions, LLC, to perform the audit. However, the audit will only cover a two-year period (2022-2024), which raises concerns. Woods worked at the CBI lab starting in 1994, and the first allegations of misconduct were made in 2014. The ACLU believes that a broader review, going back to when Woods’ misconduct was first detected, is necessary to ensure full accountability.

“The external auditors tasked with reviewing the root cause of the misconduct should be independent of CBI’s influence,” the letter states. “They should have the freedom to engage with all relevant departments, government agencies, and organizations involved in or impacted by CBI’s practices.”

Second Concern: Grant Conformance

The ACLU and KWIP also question whether CBI is complying with the requirements of its Paul Coverdell Forensic Sciences Improvement Program grant. Under the terms of the grant, the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office (JCSO) was designated as the entity to investigate allegations of misconduct at CBI. However, when KWIP filed an open records request, JCSO stated that they had never been asked to investigate CBI.

“We seek clarification as to why CBI did not involve the designated Coverdell entity in investigating Ms. Woods’ actions,” the letter asks.

Response from CBI

In response to the letter, CBI stated on November 15, 2024, that they had been working with multiple partners to ensure accountability in the investigation and compliance with their responsibilities under the grant. They promised improvements across their Forensic Services department and expressed a commitment to further reforms with the help of independent external assessors.

Increased Urgency: Murder Cases Impacted

The letter emphasizes the urgency of addressing the situation, as forensic evidence is a crucial part of many criminal trials. Delays in resolving the questions about Woods’ misconduct only prolong the harm to those affected by it.

At least three cases have already been impacted by Woods’ actions:

- In June 2024, Boulder County prosecutors agreed to a plea deal in the case of Garrett Coughlin, whose conviction for felony murder in 2019 was influenced by Woods’ questionable testing.

- In August, Douglas County prosecutors reached a plea deal with Michael Jefferson, who pleaded guilty to felony murder in the 1985 murder of Roger Dean.

- Most recently, Boulder County District Attorney’s Office has requested new DNA testing in the case of Michael Clark, who was convicted in 2012 of the 1994 murder of Marty Grisham. Woods had originally tested DNA from a lip balm jar found at the crime scene and concluded that Clark’s DNA matched, but Clark has consistently maintained his innocence.

Where is the ADC amidst all this chaos?

Moving Forward

The proposed legislation represents a pivotal moment for Colorado’s justice system. If passed, it would mark a significant shift towards holding forensic institutions accountable and ensuring that defendants’ rights are protected. However, the effectiveness of these reforms will ultimately depend on the commitment of state leaders to prioritize transparency and the voices of those harmed by systemic failures.

Colorado now stands at a critical crossroads, with an opportunity to rebuild trust in its judicial system. The outcome will depend on whether there is a genuine commitment to confronting uncomfortable truths and implementing meaningful reforms. Can the CBI ever regain credibility after such a far-reaching scandal? How many more individuals were implicated in cases involving Miss Yvonne Woods, and how many others did she train? These are questions that demand answers. It’s time for the Colorado state government to prioritize transparency, allowing citizens to fully understand the scope of the failures and to decide for themselves what steps should be taken to restore justice and accountability.

Disclaimer: This article discusses a real story involving real people and real events. It is published with the intention of informing and raising awareness about the complexities of such narratives. The content does not intend to defame or slander any individuals, and there are no legal consequences associated with the publication of this story regarding defamation or character slander.

Leave a comment