“Three things cannot be long hidden: the sun, the moon, and the truth.” — Buddha

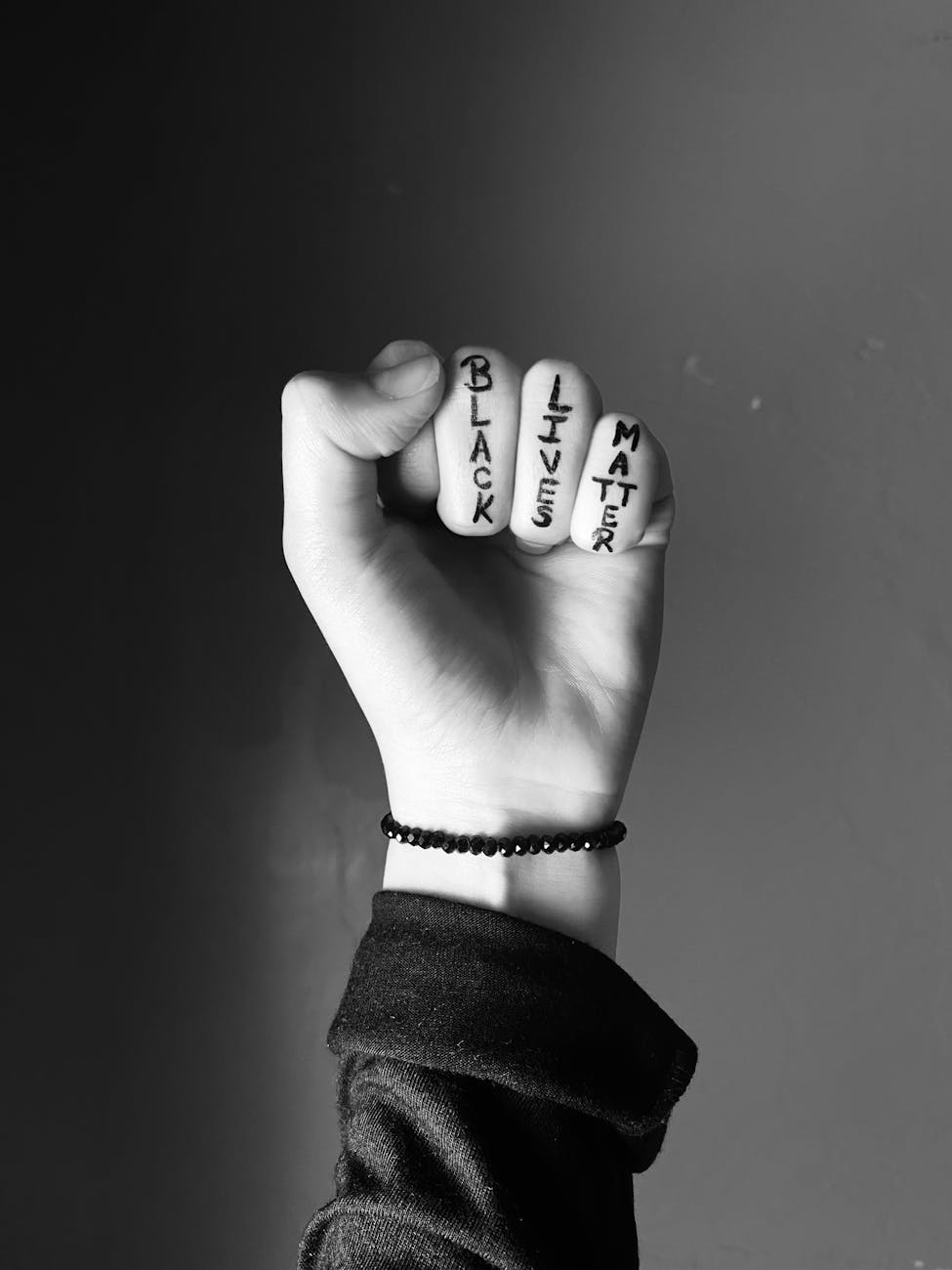

By age 18, 30% of Black males, 26% of Hispanic males, and 22% of White males have been arrested in the United States. By age 23, 49% of Black males, 44% of Hispanic males, and 38% of White males have been arrested. In the United States, Black Americans are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Black individuals make up about 12 to 13% of the U.S. population but represent a significantly larger portion of convicted individuals. For example, arrest rates for Black Americans are more than five times higher than those for White Americans. As of 2021, about 33% of the U.S. prison population is Black, even though they make up a relatively small percentage of the general population.

The War on Drugs, initiated in the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan, disproportionately impacted Black communities. Policies like mandatory minimum sentences and the “three strikes” law targeted drug-related offenses, particularly crack cocaine. Crack cocaine, more prevalent in urban Black neighborhoods, was penalized much more severely than powdered cocaine, which was more common in White communities. This disparity led to longer sentences for Black individuals, even for minor drug offenses, and fueled mass incarceration, exacerbating racial disparities in the U.S. justice system. These policies had lasting consequences on Black communities, deepening systemic inequities and perpetuating cycles of poverty and incarceration.

People lie all the time. It’s in our nature. But there are different kinds of liars—great liars, bad liars, horrible liars, and obvious liars. We encounter them every day, often without even realizing it. Lies shape our interactions, our decisions, and, unfortunately, our justice system.

After careful review of numerous cases in the United States, I have found that many are built upon lies. Not necessarily intricate conspiracies—because those would lead to clear convictions—but rather fabricated stories. Stories created by individuals who want to be seen as victims. It is rare to find a case that is truly black and white. There is always something left unsaid, a crucial detail overlooked. Often, what is dismissed as insignificant during a trial turns out to be the most crucial piece of evidence during post-conviction motions. As a result, people end up serving long sentences for crimes they did not commit.

This is what we call wrongful conviction. Some refer to it as illegal sentencing. Right now, approximately 4% of people incarcerated in the United States are serving time for crimes they did not commit. That means thousands of lives have been destroyed based on lies.

I write extensively about sex offense cases, a topic that is highly controversial. As a woman, I often face backlash for speaking on this subject. People ask me, “How can you defend people like that?” To which I respond, “What do you mean, people like that?” They are no different from those convicted of drug offenses or even murder. Yet, when I examine the statistics, I find that a significant portion of sex offense cases are wrongful convictions.

Many of these cases fall under what is often referred to as “Romeo and Juliet” laws—where a 19-year-old man is convicted for being with a 17-year-old girl. Then there are the cases where a jealous stepdaughter, seeking attention, fabricates a story. Or the drug-addicted mother who manipulates her daughter into making false accusations against a man, using the system to her advantage. There is always a twist.

The true predators, the ones who commit heinous crimes against children, women, and even men, represent only a small percentage—about 3.2%. These individuals will never be released because their crimes are monstrous. But the vast majority of those convicted of sex offenses are not the monsters the system paints them to be.

We must question the narratives presented in courtrooms. We must challenge the stories that lead to wrongful convictions. Because in a system built on lies, justice can never truly be served.

John Story

Let me tell you a story. It’s a real story, one without an end because the man who has been convicted of a crime he didn’t commit is still in prison. Year after year, he sits behind bars, waiting. It has been almost 16 years. Imagine that—sixteen years in a cell for something you never did. The jury convicted him in the blink of an eye, without truly seeing him.

As time passes, he starts questioning less and less. Hope dwindles. He tries seeking help from different organizations that claim to fight for justice, but no one takes his case. At some point, after hearing “no” so many times, he just gives up. Because in prison, “no” is the most common word. When someone finally says “yes,” it feels almost surreal, like a cruel joke. He has written countless letters to countless people, yet the responses—if they come at all—are always negative.

I won’t tell you his real name for multiple reasons. Let’s call him John. If I had to give him another name, John would feel right.

Did I meet John? Yes. And when I did, his big smile and kind eyes filled the room with a fleeting sense of happiness. But beneath that smile, deep inside, he is dying—a slow, internal death, year by year, just like the changing seasons. The grass turns gray, the leaves fall, and still, he remains in prison. Maybe, over time, he has convinced himself that this is where he belongs. Maybe his own internal voice has whispered, You’re never getting out.

You might be wondering how cases like John’s come to my attention. It’s word of mouth. My husband served 15 years in prison, and he told me about the people inside, the ones who say they didn’t do it, the ones who never got a fair chance. I’ve always said that justice isn’t blind—it doesn’t even exist. The system is broken, corrupted. But now, finally, we have the power to speak up. We are no longer afraid to ask questions, to demand answers.

And I am not afraid to ask on behalf of John. Because John doesn’t belong in prison. He is serving someone else’s time while the real perpetrator enjoys life. Sixteen years is enough. John has so much to offer. He is quiet, polite, educated, and never angry. He thinks before he speaks. He isn’t explosive. He cares for others, helps others inside the prison. Despite his size—he’s not a small guy—he remains almost invisible, yet visible at the same time. His family loves him. His sisters support him. And it is time for John to finally get justice. It is time for John to go home.

But El Paso County—one of the most corrupt counties in Colorado, in my opinion—turned him into something he is not. The judge, the one who was supposed to uphold integrity, the one who was supposed to be educated and impartial, had the audacity to call him a monster. What kind of judge does that? What kind of people are sitting on those benches? Have you ever thought about it? I never questioned judges before, not until I became part of reentry work, not until I saw the system from the inside. Now, every time I step into a courtroom, I see them differently. I watch their body language, listen to the way they speak. Do they truly understand what’s happening? Are they fair? Are they educated? Are they kind? I find myself profiling them, forming my own opinions.

And too often, my conclusion is simple: This judge is a disaster. This judge is a shitshow.

John deserves better. He deserves freedom. And I will not stop speaking for him until he gets it.

The Man Who Waits: A Story Without an End

This article may leave you questioning more than a few things, and that’s precisely the point. What I’m about to bring to light is not merely a legal analysis or a courtroom presentation. It’s my interpretation of the facts, based on the discovery materials—documents that haven’t entered the court system yet and might never make it there. So, what you’ll read here is a perspective, not a final judgment. I’m not alleging anything; I’m just offering what seems to be true given the information at hand.

This story isn’t a simple one, and it raises questions that I can’t definitively answer. One of the biggest questions that persists through every step of this is: Who is the real victim? We throw the word “victim” around like it’s an answer to everything, don’t we? Victim rights, victims of this, victims of that. But who is the real victim in any case? I’ve tried to find the definition of a victim in legal terms—looking at Supreme Court cases, looking at regular cases—and the more I search, the more I realize I don’t ever get a clear answer. The term feels incomplete, elusive.

Take John, for example. I want to tell you his story, and I’ll be honest, I can’t help but see him as a victim. But not in the conventional sense. John is a victim of the system—the very system that was supposed to protect him. The system played him. His defense attorneys failed him. They were more interested in getting paid than in getting him a fair trial. The reality is that public defenders, those supposedly fighting for the underdog, often fail miserably. They show up for court with a briefcase and a promise to defend, but they don’t know the case, they don’t understand the stakes, and they certainly don’t care.

They’re not there to win; they’re there to get the job done. They might spend five minutes with you before the hearing, offering up the most half-hearted defense imaginable. If a high-profile case lands on their desk, they shift their focus. The stakes change, and suddenly, your case is less about justice and more about their next step on the career ladder. Public defenders are, in many ways, a joke. It’s almost like getting a “discount” lawyer—if that lawyer even shows up at all. In the end, they don’t fight for you, and you end up being sold out.

I’ve seen it firsthand, and it’s hard to ignore. In some cases, I think defense attorneys might be worse than district attorneys. At least with a DA, you can see their angle; they’re in it for the prosecution, they’ll argue their case, even if they’re bending the truth to do it. But with a public defender? There’s no fight. They’ll walk into a courtroom unprepared and unmotivated. They don’t care about your case. They care about getting their paycheck and moving on to the next one.

So, where does that leave John? He’s the one who paid the price for the negligence, for the system’s failure. He’s the one who’s left holding the bag while everyone else moves on. Was he truly a perpetrator? Or was he, like many others, just a casualty of a broken system? Maybe it’s time we start asking the right questions. Maybe the real victims are the ones who never even had a chance to begin with.

Johns Discovery

As I sifted through John’s discovery, I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed. It was just a fraction of the full case file—900 pages filled with dense, convoluted details. Yet, certain elements immediately stood out to me. The victim’s rape kit, for instance, had been repeated at least five or six times throughout the file. Why? Was it a mistake? An attempt to emphasize a particular narrative? The redundancy made it all the more perplexing.

Other testimonies were also duplicated, scattered across different sections, making it nearly impossible to track a coherent timeline of events. The entire case file seemed haphazardly compiled, as if the detective handling it had done a rushed, sloppy job. And as I turned each page, my suspicion grew stronger. I was about to name the detective responsible for this mess when another troubling thought hit me—why was so much emphasis placed on the victim’s story? Why did the case seem so desperate to reinforce a particular narrative?

Now, let me tell you about the so-called victim. I have no doubt that she is a victim—but not in the way the prosecution claims. She is a victim of her own agenda, her own fixation, her own lies. And in the end, karma caught up with her.

This wasn’t the first time she had claimed to be sexually assaulted. It was the third. But unlike the previous two times—when she had been exposed as a liar—this time, she succeeded. This time, her deception had a victim: John.

People like her exist, and they are dangerous. Some suffer from mental health issues, some are lost in fantasy, some are driven by greed, rejection, or anger. Manipulation becomes second nature to them, and over time, they convince even themselves of their fabricated reality. They become trapped in their own pathological lies, carrying them forward until someone else pays the price.

In this case, that someone was John. Three times was the charm. And now, an innocent man faced the consequences of a justice system that failed to separate truth from illusion.

In Colorado, victims of sexual assault are not legally prohibited from changing their testimony. However, recanting or altering testimony can have significant legal implications. Prosecutors may proceed with the case if they believe sufficient evidence exists, even without the victim’s cooperation. Additionally, if a victim recants and admits to providing false information initially, they could face charges such as false reporting, a class 3 misdemeanor under Colorado law.

Let me tell you how John got convicted, and I will provide some of the statements from the alleged victim. I say “alleged” because I do not consider her a victim—I believe she played her role well. She knows for a fact that the man serving time in prison for the crime she accused him of is the wrong person. She knows that the man imprisoned is not the one who harmed her.

However, the alleged victim is far from innocent. It seems to me that she was dishonest not only with the police department but also with her own family. One of the most striking things about this case is her family’s reaction. When something traumatic happens, and you call your parents—your mother, your father—to tell them you’re in the hospital because something horrible occurred, do they question you? Or do they immediately get in the car and rush to your side to ensure you’re safe? Which one is it?

Here is an excerpt from a statement:

“When I arrived at the hospital, I went into her room. Ms. S was standing up, talking on the phone. She was crying as she spoke. At one point during the conversation, she said, ‘Mom, I need you here,’ so I believe she was speaking to her mother. She was talking very fast, saying that she had been followed by a man who attacked and raped her in a field. She was begging for her mother to come be with her. She also said, ‘I have been raped, and you’re talking about gas,’ still crying.

Ms. S sat down on the bed and handed me the phone, asking me to speak to her mother. When I identified myself, a female voice said she was Emily’s mother and asked what was going on. She said she could not understand what Emily was saying, except that she had been raped. She then asked me if this was true.

I explained that Emily was at Memorial Hospital and that I had not yet spoken to her, so I did not know the details—only that she claimed to have been sexually assaulted. Emily’s mother said she would try to find a ride to the hospital and asked me to inform Emily. Then she hung up. I told Emily that her mother was attempting to come to the hospital.”

Do you know where the victim’s mother was when she asked the investigating police officer whether the accusation was true? She asked this because her own daughter had previously lied—twice—about being sexually assaulted by two different men. Both accusations turned out to be false.

Unfortunately, the defense in John’s case was too weak to present this information at trial. How is that even possible? Establishing the credibility of a witness is essential—otherwise, anyone can say whatever they want, and innocent people can be falsely accused.

There must be some form of protection for those who are accused of a crime, not just for the victims. Right now, we have so many protections for victims that I don’t even know how these cases can be properly handled in court. There are so many restrictions—what can and cannot be done—that seeking true justice has become nearly impossible.

We know when people are lying, and in this case, she did. What exactly happened, I do not know, but her story simply does not make sense.

“Speaking Like a Thug”: A Questionable Testimony

In reviewing the testimony of the alleged victim in John’s case, one particular statement stands out:

“She said that she goes out to the clubs every other weekend and she is frequently around black males, that are his type, and she said that he talks like a normal ‘thug.’”

This description raises a crucial question—what exactly does it mean to “speak like a thug,” and how does such a vague, racially charged characterization hold any weight in a criminal investigation?

Breaking Down the Victim’s Statement

The victim’s recollection is highly detailed. According to the case discovery, she claims to have had a conversation lasting 7 to 10 minutes with her alleged attacker—long enough to learn personal details, such as that he was married and had two children, a boy and a girl. That alone is unusual for a violent assault scenario.

If this was truly a case of sexual assault, how much time was spent conversing versus resisting? How did she manage to recall so many personal details while allegedly being under distress? And more importantly, how does one define speaking “like a thug”?

The Problem with “Speaking Like a Thug”

The phrase “speaking like a thug” is a subjective, racially loaded stereotype. Generally, it refers to:

- Slang and informal language – Common phrases used in urban communities, such as “ain’t” or “yo.”

- Aggressive or confrontational tone – Speaking in a way that sounds tough or dominant.

- Grammar and pronunciation – Speech that may be unpolished or non-standard.

- Cursing or street jargon – Using language associated with street culture.

These elements do not indicate criminal behavior but are often unfairly used to profile certain groups.

A Case of Racial Profiling?

Given that the alleged victim explicitly stated she was familiar with black men who “fit his type,” is it fair to question whether she was engaging in racial profiling? Could it be that she misidentified or even deliberately targeted a specific group?

Her testimony includes strikingly detailed descriptions of her alleged attacker—including the size and condition of his genitals “ big, thick long penis” and distinct spots around his eyes. These are intimate observations that seem inconsistent with a traumatic sexual assault scenario, where victims often report dissociation or memory gaps.

Too Many Details, Not Enough Truth?

Survivors of sexual assault frequently describe a state of shock, fear, or dissociation. They freeze, they close their eyes, and they often struggle to recall specific details. Yet, in this case, the alleged victim remembered intricate details about her attacker’s body, clothing, and even his family life.

This raises further doubts:

- Did she know the person she was accusing?

- Was this truly a case of rape, or was she too intoxicated to fully comprehend the situation?

- Did she initially consent and then change her mind later, perhaps due to guilt or regret?

The troubling reality is that John’s case was built on a foundation of questionable statements, racial undertones, and a testimony that feels more like a rehearsed script than a true account of trauma. If the alleged victim truly experienced an assault, the evidence should reflect that. But when the details are overly vivid, when descriptions veer into stereotypes, and when the timeline doesn’t add up—it’s time to question the narrative.

Justice should never be determined by vague descriptions or racial stereotypes. It should be determined by truth.

The Case Against Detective Jeff Huddleston: A Legacy of Corruption and Misconduct

In the world of law enforcement, there are those who seek justice and those who manipulate it for their own gain. Detective Jeff Huddleston, a longtime member of the El Paso County “good old boys” club, falls into the latter category. Assigned to a 2009 case, he built his career on questionable tactics, shortcuts, and a blatant disregard for due process. His actions led to the wrongful conviction of John, a man whose past may not have been spotless but who was undoubtedly innocent of the crime for which he was sentenced.

A Dirty Cop Playing a Dangerous Game

Huddleston, who had been on the force for over two decades, played fast and loose with the rules. His involvement in John’s case raised countless red flags. Despite the crime occurring in 2009, John wasn’t arrested and indicted until 2011—by none other than Huddleston himself. The delay wasn’t due to new evidence or a breakthrough in the investigation. Instead, it was the result of a detective who was determined to close a case, regardless of whether the person he targeted was guilty.

His tactics were not just unethical—they were illegal. While John was in county jail, Huddleston attempted to question him without an attorney present. Posing as a “friendly conversation,” this clear violation of John’s rights was an underhanded attempt to extract information that could be twisted into evidence. It was a classic case of manipulation, a dirty cop testing the limits to see what he could get away with.

A Pattern of Misconduct

Huddleston’s involvement in the case wasn’t an isolated incident. His entire career seemed to be riddled with reckless behavior and a failure to uphold the principles of justice. The discovery files on his past cases tell a story of a detective who was more interested in securing convictions than uncovering the truth. His position in the Unit for Sexual Assault Investigations (UNET) raises serious concerns—did he even understand the job he was supposed to be doing? Or was he more interested in playing the victim for the victim, fabricating cases where none existed?

John was an easy target. Yes, he had prior run-ins with the law—possession of marijuana, driving with a suspended license, accusations of robbery. But none of those offenses made him guilty of the crime he was ultimately convicted for. That didn’t matter to Huddleston. His number-one suspect was already behind bars, and rather than putting in the work to solve the case, he built a flimsy argument against John, knowing a conviction was all that mattered.

The “Trophy” Conviction That’s Falling Apart

For detectives like Huddleston, a conviction is a trophy. It doesn’t matter if the person is innocent. What matters is adding another case to their record, another closed file on their desk. But the problem with wrongful convictions is that, sooner or later, the truth comes to light.

As more people begin to scrutinize Huddleston’s work, his legacy is starting to crumble. His shortcuts, fabrications, and willingness to railroad an innocent man are being exposed. The “trophy” he thought he won is nothing more than a stain on his career.

It is uncertain if Huddleston is still alive today, but one thing is for sure—karma does not forget. The truth has a way of resurfacing, and when it does, the detectives who built their careers on lies will have nowhere to hide.

John deserved better. Justice should never be about convenience or personal gain, yet Huddleston made a career out of twisting the system in his favor. Now, as his past is being unearthed, the question remains: how many other innocent people were locked away because of his reckless, racist, and corrupt methods?

The time has come to examine every case he touched and demand accountability for the lives he destroyed.

The Forgotten Truth: A Case of Assumptions and Oversights

The night of November 22, 2009, was cold, dark, and filled with unanswered questions—questions that should have been asked but never were. The case that unfolded in the early hours of that morning would change lives, yet it was built on shaky ground, missing key details that no one seemed to care about.

The Call That Started It All

Mr. H made the call. He reached out to the police, concerned about his cousin, Emily, who had been frantically calling him for a ride. She was walking alone, intoxicated, after a night that had spiraled out of control.

The facts were simple. Emily had been drinking—not just beers, but shots, enough to impair her judgment. She had been at someone’s apartment, had an argument, and stormed out. She didn’t want to wait for a ride. She wanted out. That was her choice.

But what no one asked—what no one ever seemed to care about—was how impaired she truly was. Where was the toxicology report? The discovery file was thick, filled with details about the rape kit, bruises, and medical examinations. They combed through evidence of torn clothing, broken straps, and even a Walmart bag with scattered clothes, boots, and a single flip-flop—as if that alone told the story. But nowhere in that file was a simple answer to the most pressing question: What was in Emily’s system?

Assumptions Over Facts

Emily was presented as a victim, but the case was built on selective details. She was out drinking, making impulsive decisions, and then walking alone in the middle of the night. Was she in danger? Maybe. But was she telling the whole story? That part was never questioned.

Law enforcement focused on what they wanted to see—injuries, torn fabric, and the emotional testimony of a woman who had been drinking heavily. The bruises could have come from anywhere. The broken bag? Could have been from a fall. But none of that mattered because the investigation had already decided the outcome before the real questions were asked.

The Missing Pieces

- No blood alcohol content report.

- No drug screening.

- No follow-up on her argument at the apartment.

- No investigation into whether her memory was reliable.

Instead, they built a narrative around bruises, clothes, and a scattered Walmart bag. A party girl turned victim overnight—because that’s the story they wanted to tell.

But the truth has a way of resurfacing.

Someone, someday, would go through the case file and ask the right questions. And when they did, they wouldn’t just see a victim—they’d see a broken investigation, a rushed case, and a truth that had been buried beneath assumptions and omissions.

The Forgotten Victim: How the System Created a Criminal

In the shadows of El Paso County, Colorado Springs, 2011, justice wasn’t about truth—it was about perception. It was about power, about race, about who fit the profile and who didn’t. The system needed a conviction, and John was the perfect target.

The Case That Was Never Meant to Be

It started with Emily, the so-called victim. She was well known in the local party scene—couch to couch, bar to bar, drink to drink. She was the girl everyone knew but no one really knew. She had been in that crowd before, surrounded by the men she claimed to fear, yet she kept coming back. Was she really afraid? Or was she playing a different game?

That night, Emily drank—beers, shots, whatever was poured. She got into an argument. She left, alone, walking the streets in the early hours of the morning. By the time the police got involved, her story had already taken shape. She was the victim. She was the fragile, intoxicated woman who had been wronged.

But who was questioning her? Where was the toxicology report? Where was the proof? Why was her word enough to destroy someone’s life?

John: The Perfect Suspect

John never stood a chance. He was a Black man in El Paso County, standing out in a sea of white faces and cowboy hats. They saw him before they even heard him. To them, he was already guilty.

When the police wanted an arrest, they made sure it was him. It didn’t matter that his height didn’t match the description, that the story was full of contradictions, that Emily had a history of crying wolf when things didn’t go her way. None of that mattered. The detective had a suspect, and that suspect had a name.

John’s face hit the papers. The SWAT team was sent to take him down like a dangerous criminal. His family was dragged through the mud, his bail set so high it might as well have been a life sentence already. Because once the system decides you’re guilty, there’s no turning back.

A Defense That Never Existed

John had a public defender. Chad Miller. A name that echoed through the halls of injustice in El Paso County. The same man who had “defended” Jaime Duran, a man now serving life without parole—because Miller had conveniently forgotten to present evidence that could have changed everything.

John’s case followed the same script. No real defense. No real chance. Just another name to check off the list.

And while the so-called victim was being prepped—coached on how to cry, how to dress, how to tell her story in just the right way—John was sitting in a cell, already convicted in the court of public opinion.

Justice, or Just Another Name on a List?

How many men like John had been fed into the system, chewed up, and spat out as criminals because someone needed a conviction? How many times had victim advocates groomed a story until it fit their needs, ignoring the facts that didn’t?

The system wasn’t designed to protect the innocent. It was designed to protect itself.

And John? He was just another casualty.

Leave a comment